They used to have a doomsday clock, and for all I know they still do. Every once in a while it would show up in a newspaper article, saying that the doomsday clock during such and such a crisis had edged to seven minutes to midnight, with midnight signifying Armageddon. The worry then was atomic war, and we all worried about atomic fallout and atomic winter and other such nasty stuff. Then the Soviet Union collapsed and we put on a happy face, revved up our economies, went on the net, turned in our guitars for electric basses and stopped worrying about Armageddon timepieces.

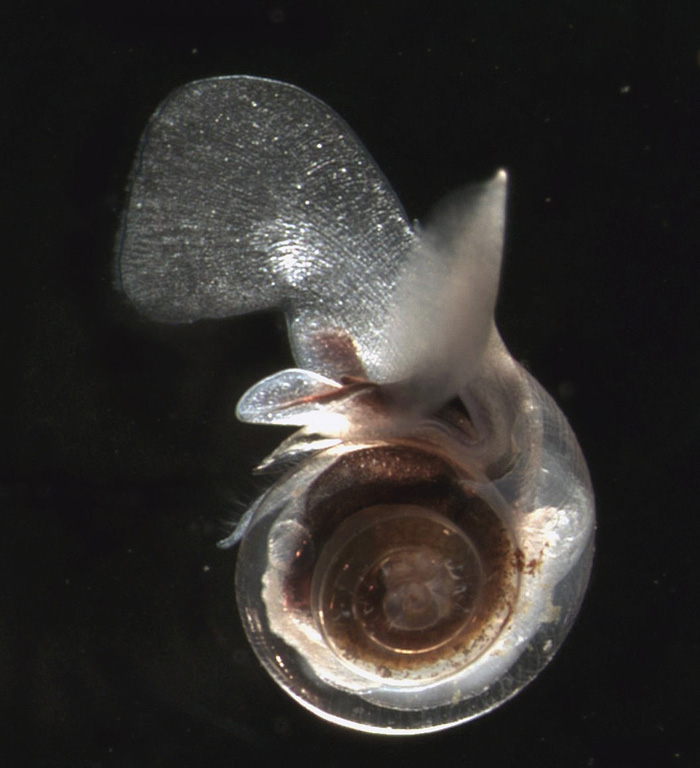

Well, it's time to reset the doomsday clock once again. This time set it for 2030. That's the year when the pteropods start dying.

I knew that would worry you.

Gretchen Hofmann, a molecular ecologist and biology professor at the University of California Santa Barbara, calls pteropods the "potato chip" of the ocean because so many species feed on them. Fish eat pteropods, penguins eat fish: it's the grand scheme of life. But if the pteropods die, then there are fewer fish, then the penguins start to croak. That's the not-so-grand scheme of death.

And of course it's not just penguins we have to worry about. We're not really sure how many species would be endangered if the pteropods die. Lots, most likely, since critters at the pteropod end of the food chain tend to ultimately feed species all the way up the food chain to us, me and you.

So what is it that's going to do in the pteropods? Carbon dioxide. Yep, the same gas that's bringing us global warming.

You see, there is direct relationship between carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere and the carbonate chemistry of the surface of the oceans. The surface of the oceans, those places where surface light can still be seen, is where most ocean life is found. You don't want to mess with it. But unfortunately high carbon levels do mess with it, and in critical ways.

The ocean, you see, is where a lot of the carbon that our global civilization produces winds up. Something between 33% or 40% of the surplus carbon produced in the 200 years since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution has wound up in the ocean, an amount totalling something like 120 billion tons. At present some 25 million tons of carbon dioxide dissolve in the ocean every day. That's right. Every day.

Okay, that's a good thing, because otherwise all that carbon would be in the atmosphere contributing to warming.

But it's a bad thing because all that excess carbon is also making the ocean acidic.

Toss a piece of chalk into a bottle of vinegar. Watch it dissolve. Now imagine that piece of chalk is a crab. Watch the crab's shell dissolve. Watch the crab die. (Now please don't go tossing crabs into acid. Take my word for it. It's the same effect as with the chalk.)

Too much CO2 in the ocean leads to the formation of carbonic acid, and the more carbonic acid, the less carbon bicarbonate, which shellfish and pteropods use to build shells. These shells effectively sequester carbon dioxide, meaning that it isn't going to go back into the atmosphere to contribute to global warming. When pteropods die, their shells drift down to the ocean floor and just lie there, keeping the carbon in the shells out of circulation. That's a good thing.

Stopping that process, that's a bad thing.

Well, lately a report has come down which more or less pinpoints when that process stops, when the atmospheric carbon is too high, and the oceans consequently become too acidic to support shellfish and pteropods. Some scientists say that will happen when atmospheric carbon dioxide levels reach 450 parts per million. According to current projections, that level will be reached in 2030.

Then forget oysters and clams, forget cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh. The entire ecology of the ocean will probably begin to collapse. And since the entire planet is dependent in one way or the other on the oceans, humanity won't fare too well, either.

Set your clocks for 2030. Doomsday melting your lobster dinner.

Or maybe we really will change our ways before that happens, stop buying more and more stuff, stop driving to work, stop jetting all over the place, stop sending immense amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, stop placing the economy ahead of the planet.

And maybe we'll start caring, I mean really caring, money-where-your-mouth-is type of caring, about the future of the planet.

You know, the future, where our children and grandchildren are going to have to live.

Oh yeah, we'll change. Soon.

Sure we will.

Addenda: The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has recently reset the Doomsday Clock to 6 minutes to midnight (from 5) in response to recent promises by world governments to fight climate change and the actions of President Obama in respect of world peace (Afghanistan notwithstanding.) Dependent, of course, on whether any of those promises are fulfilled.

_____________________

Well, it's time to reset the doomsday clock once again. This time set it for 2030. That's the year when the pteropods start dying.

I knew that would worry you.

Gretchen Hofmann, a molecular ecologist and biology professor at the University of California Santa Barbara, calls pteropods the "potato chip" of the ocean because so many species feed on them. Fish eat pteropods, penguins eat fish: it's the grand scheme of life. But if the pteropods die, then there are fewer fish, then the penguins start to croak. That's the not-so-grand scheme of death.

And of course it's not just penguins we have to worry about. We're not really sure how many species would be endangered if the pteropods die. Lots, most likely, since critters at the pteropod end of the food chain tend to ultimately feed species all the way up the food chain to us, me and you.

So what is it that's going to do in the pteropods? Carbon dioxide. Yep, the same gas that's bringing us global warming.

You see, there is direct relationship between carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere and the carbonate chemistry of the surface of the oceans. The surface of the oceans, those places where surface light can still be seen, is where most ocean life is found. You don't want to mess with it. But unfortunately high carbon levels do mess with it, and in critical ways.

The ocean, you see, is where a lot of the carbon that our global civilization produces winds up. Something between 33% or 40% of the surplus carbon produced in the 200 years since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution has wound up in the ocean, an amount totalling something like 120 billion tons. At present some 25 million tons of carbon dioxide dissolve in the ocean every day. That's right. Every day.

Okay, that's a good thing, because otherwise all that carbon would be in the atmosphere contributing to warming.

But it's a bad thing because all that excess carbon is also making the ocean acidic.

Toss a piece of chalk into a bottle of vinegar. Watch it dissolve. Now imagine that piece of chalk is a crab. Watch the crab's shell dissolve. Watch the crab die. (Now please don't go tossing crabs into acid. Take my word for it. It's the same effect as with the chalk.)

Too much CO2 in the ocean leads to the formation of carbonic acid, and the more carbonic acid, the less carbon bicarbonate, which shellfish and pteropods use to build shells. These shells effectively sequester carbon dioxide, meaning that it isn't going to go back into the atmosphere to contribute to global warming. When pteropods die, their shells drift down to the ocean floor and just lie there, keeping the carbon in the shells out of circulation. That's a good thing.

Stopping that process, that's a bad thing.

Well, lately a report has come down which more or less pinpoints when that process stops, when the atmospheric carbon is too high, and the oceans consequently become too acidic to support shellfish and pteropods. Some scientists say that will happen when atmospheric carbon dioxide levels reach 450 parts per million. According to current projections, that level will be reached in 2030.

Then forget oysters and clams, forget cockles and mussels, alive, alive, oh. The entire ecology of the ocean will probably begin to collapse. And since the entire planet is dependent in one way or the other on the oceans, humanity won't fare too well, either.

Set your clocks for 2030. Doomsday melting your lobster dinner.

Or maybe we really will change our ways before that happens, stop buying more and more stuff, stop driving to work, stop jetting all over the place, stop sending immense amounts of carbon into the atmosphere, stop placing the economy ahead of the planet.

And maybe we'll start caring, I mean really caring, money-where-your-mouth-is type of caring, about the future of the planet.

You know, the future, where our children and grandchildren are going to have to live.

Oh yeah, we'll change. Soon.

Sure we will.

Addenda: The Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists has recently reset the Doomsday Clock to 6 minutes to midnight (from 5) in response to recent promises by world governments to fight climate change and the actions of President Obama in respect of world peace (Afghanistan notwithstanding.) Dependent, of course, on whether any of those promises are fulfilled.

_____________________